In the fall of 1347, rat fleas entered Italy via the Black Sea, carrying the first stirrings of Bubonic Plague. Firsthand accounts of this crisis are scarce, but reveal a country, and later a continent fully submerged in chaos. Devastation was swift. Panic cued more panic. Cities crumbled and those wealthy enough, or lucky enough to escape, did so. For the rest, waiting it out was the only option.

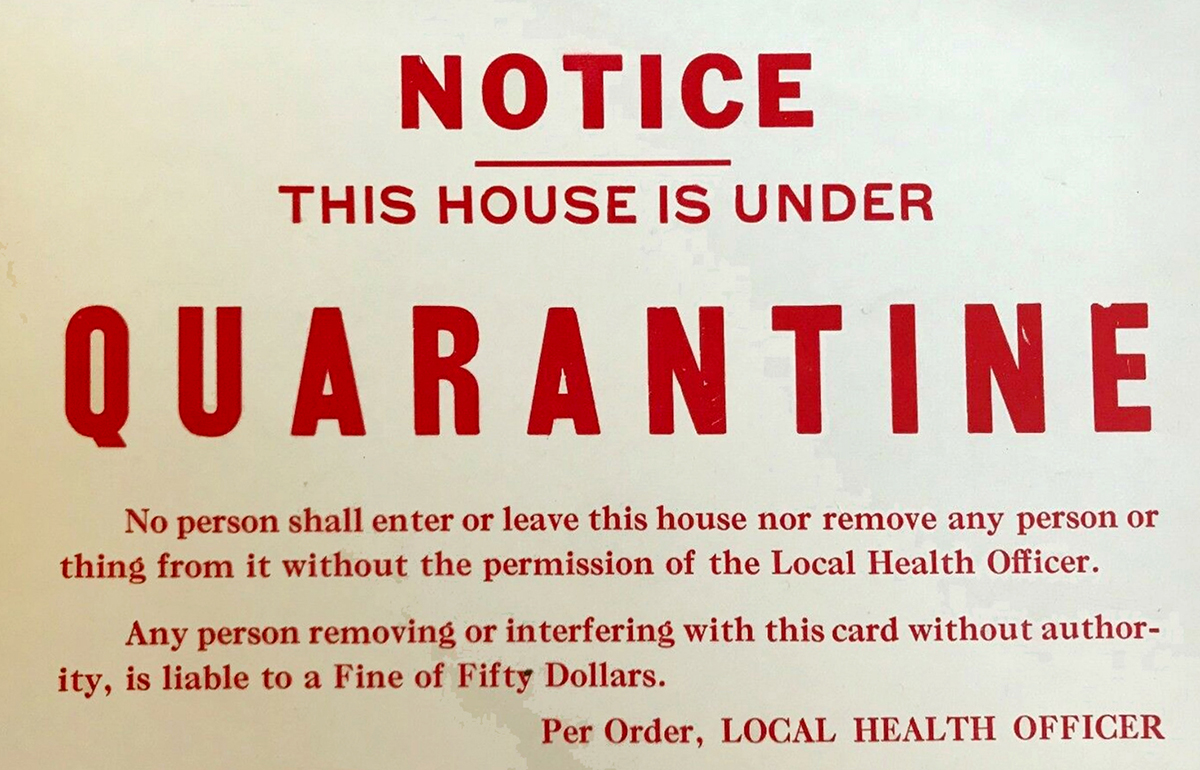

Enter quarantine—from the Italian quaranta giorni, or forty days—a time-stamped sanction on restricted movement, established by city officials in Venice and Milan to stop the spread of the virus that would later become known as the Black Death. A symbolic number (and originally chosen for its biblical associations) forty is also the number of weeks in a full-term pregnancy, and the number of days in the life of a plant. Gestation, like germination, is guided by a sage internal metronome, just like planetary cycles and weather patterns, the change of the equinox and the phases of the moon.

Adopt the pace of nature, Emerson wrote. Her secret is patience.

Not as easy as it sounds—even (perhaps especially) for nature. Our current retreat from public life has created an activity vacuum, the kind that nature abhors. And so it is that the animal kingdom—keepers of their own flawless internal metronomes—are taking notice. Monkeys are rioting in rural Thailand. Squirrels have taken over a park in Santa Monica. Jackals are storming the public squares in Tel Aviv, while ducks appear to be nesting in Venetian lagoons. Wild deer graze in Northern India, wild goats thrive in Northern Wales, and hedgehogs are taking to the roads across England.

Not so patient, those humble creatures. They’re hungry for food, while we’re perhaps hungry for a few other things, like the restoration of some semblance of a normal, non-quarantined life.

But wait.

What if waiting was the point?

I said to my soul, be still, and wait without hope

For hope would be hope for the wrong thing; wait without love

For love would be love of the wrong thing; there is yet faith

But the faith and the love and the hope are all in the waiting.

Wait without thought, for you are not ready for thought:

So the darkness shall be the light, and the stillness the dancing.

Disillusioned by profound and ponderous questions about science and religion, East Coker is the second poem in T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets: it’s a dazzling, lyrical prayer about many things, including the idea that humans are deficient, disorderly, and lost.

But now, consider these words not as a cue to seek redemption, but as an invitation to reverse the engine. Waiting not as punitive, but promising.

To repeat. Adopt the pace of nature, Emerson wrote. Her secret is patience.

And so, we wait. We wait for quarantine to lift, for the animals to retreat, for the world to reopen. We wait for social distance to be a relic of a distant time, not a way to measure distance from each other. But to wait inside is also a chance to go inside, and stay there for awhile, resetting our own internal metronomes with the grace, understanding, and self-knowledge that only humans possess. Let the animals riot. Let the seasons change and the skies get dark. But at this place, at this moment of time, all mankind is us, whether we like it or not, wrote Samuel Beckett. Let us make the most of it, before it is too late.

The Self-Reliance Project is a daily essay about what it means to be a maker during a pandemic. Sign up to get it delivered to your inbox here.