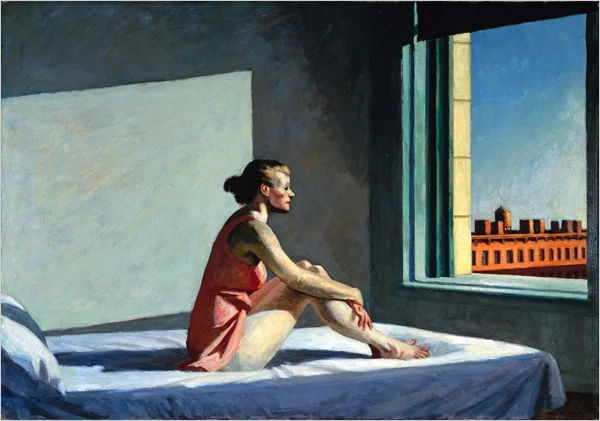

Edward Hopper, Morning Sun. 1952. (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.)

As a child growing up in Paris, I was envious of classmates whose parents worked for the American embassy because they could shop at the American commissary and buy American food. No matter that this was Paris, city of gastronomic delights, a patisserie on every corner. No: I was ten years old, and I longed for graham crackers.

The heart wants what it wants.

Emily Dickinson wrote those consoling words to a friend whose husband was about to leave on an extended voyage. (Not to see what we love, she wrote, is very terrible.)

Dickinson wasn't wrong. Wanting what is not possible—no matter how you define your object of desire—is a recipe for disappointment. It’s also a very real consequence of extended quarantine. Captive during the pandemic and forcibly distanced from all that we know and love, the wanting heart is, arguably, left wanting.

Enter longing: the yearning for what we can’t have. Longing fuels our appetites, frames our wishes, feeds our love affairs—and makes us sad. Longing for the things we can’t connect to makes us even more sad, and sadness reboots that essential, primordial longing. A vicious cycle. (And not a very actionable one.)

But now think about studio practice, and imagine, conversely, how limitations in a project brief yield new opportunities for expressing ideas. This is a classic concept in art and design education—a pedagogical variant, if you will, of less is more—and one well worth considering as a model for creative life under lockdown. Can disaster be generative? Can deprivation be redemptive? Can less really be more?

Human beings thirst for companionship and contact. We are, after all, a social species, craving exchange and communion, and resisting, by any means necessary, that which makes us feel cast adrift, disconnected, and lonely. (“Loneliness is grief, distended,” Jill Lepore tells us. “We hunger for intimacy. We wither without it.”)

Hunger and withering: that’s us. But to focus on what’s missing might just be missing the point.

Loneliness is a social epidemic that preceded—and will long outlive—this or frankly any pandemic. Dwell on that if you wish, but this might also be a moment for inventing new ways to live and work: alone, not as a forgotten fragment of who you were before, but as a whole, grounded, autonomous, independent, and highly individuated person.

Imagine confinement as a catalyst for creativity. What might that look like?

Not to have access to what we want may indeed be very terrible. But where there are possibilities, there is hope. Desire, Emerson writes, is possibility seeking expression.

What an exquisite reminder that the mind is flexible, the imagination ever present, and the heart capable of infinite expansion. There are so many ways to see. So many ways to be. And so very many ways to love.