Two weeks ago I made a stop in Topeka, Kansas, where I was fortunate to have had a chance to visit The Mulvane Art Museum at Washburn University. Though I was there on other business, I happened upon a photography exhibit that was in the process of being de-installaed. While many images were already down and readied for shipping, I saw a single large print lying against the wall that was so haunting and compelling I had to know more.

The Director of the Mulvane, Connie Gibbons, told me the work was by Daniel W. Coburn, a photographer who lives and works in nearby Lawrence. Daniel is an Assistant Professor of Photo-Media at the University of Kansas, and received his BFA degree six years ago from Washburn. He received an MFA from the University of New Mexico and shortly thereafter the German publisher Kehrer Verlag published his first monograph The Hereditary Estate.

The striking image I saw that day in the gallery was of the photographer’s mother. She was wearing what appeared to be a veil, but it was simply the shadow of her black hat. Her eye makeup was thick and broken, the pores of her skin visible in a shot so close any viewer might feel uncomfortable. I was inexplicably drawn to it.

Coburn will tell you that his work is about family. It’s there that he finds the connections and intimacy that allows him passage into the personal space of his father, mother, and siblings. Their openness and ability to lay bare their lives is what makes these images so powerful.

According to Coburn, he was a teenager when he learned of some rather dark secrets about his family—that his mother and aunt were physically abused at the hands of their domineering father (his grandfather); there was the suicide of his father’s brother; and the subsequent guilt his own father has carried believing that he could have possibly prevented it. All of this, compounded by alcoholism on both sides of his family, led Coburn to approach the idea of “family” in a way that is both intimate and haunting. Coburn calls his family photographs, especially those of his nieces and nephews, a gateway to “the remnants of lost innocence.”

In his series entitled The Hereditary Estate, Coburn uses his own family snapshots (and anonymous ones he has found at estate sales) next to his own images, a dialogue that seems to provide a counterpoint his struggle with that of the ideal family. His images charge head on to reveal the banality and difficulty of life, the myth of achieving the American Dream, and the complex understanding of family. Nothing is glamorized in Coburn’s photography. You could say this body of photographs finally sets his personal family photo album straight. It’s honest and refreshing work.

Coburn is an exciting new photographer who just may be a short step or two from wide acclaim. I look forward to following his career.

Judgement Veil from the Hereditary Estate Series | 2012

Mom Cooling Off in the Pool, from the Next of Kin Series | 2012

Dad's Authority from the Next of Kin Series | 2012

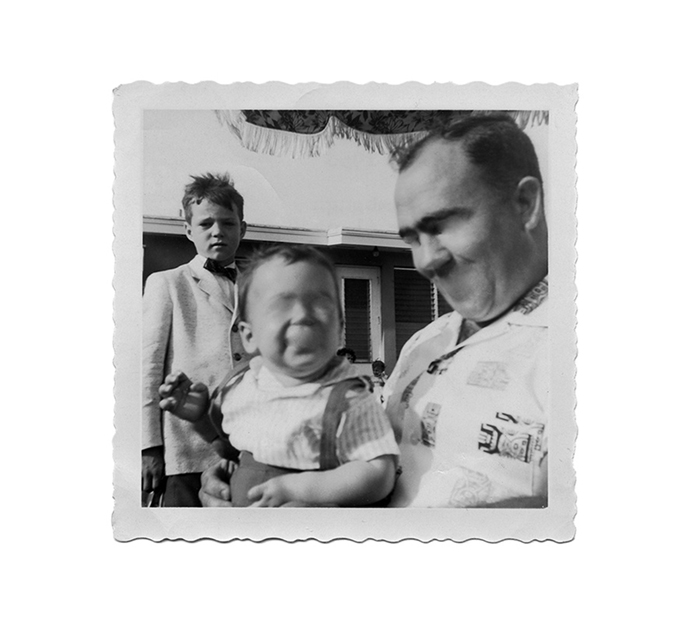

Untitled, from the Hereditary Estate Series; found snapshot | c. 1955

Take of the Tolls from the Hereditary Estate Series | 2012

Untitled, from the Hereditary Estate Series; manipulated found snapshot | c. 1955

Jake Plays wth Fire, from the Hereditary Estate Series | 2012

Dad Preparing His Meat, from the Next of Kin Series | 2012

Mom's Clutch, from the Next of Kin Series | 2012

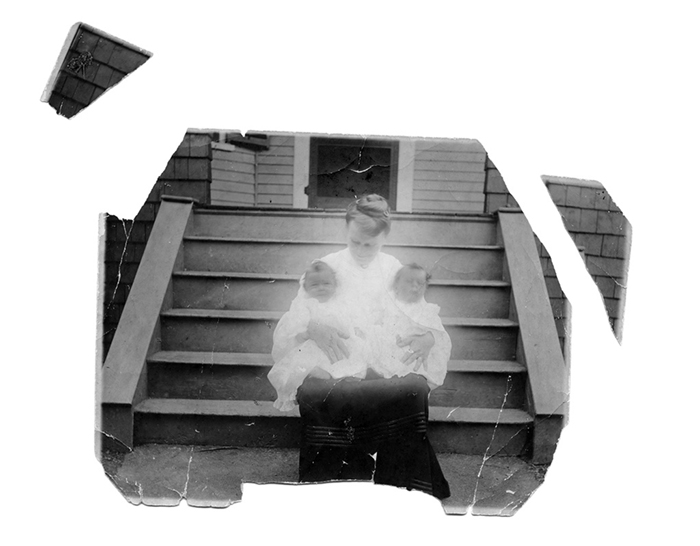

Untitled, from the Hereditary Estate Series; manipulated found snapshot | c. 1935

Ascent, from the Hereditary Estate Series | 2012

Lover's Embrace, from the Hereditary Estate Series | 2012

Communion, from the Hereditary Estate Series | 2012

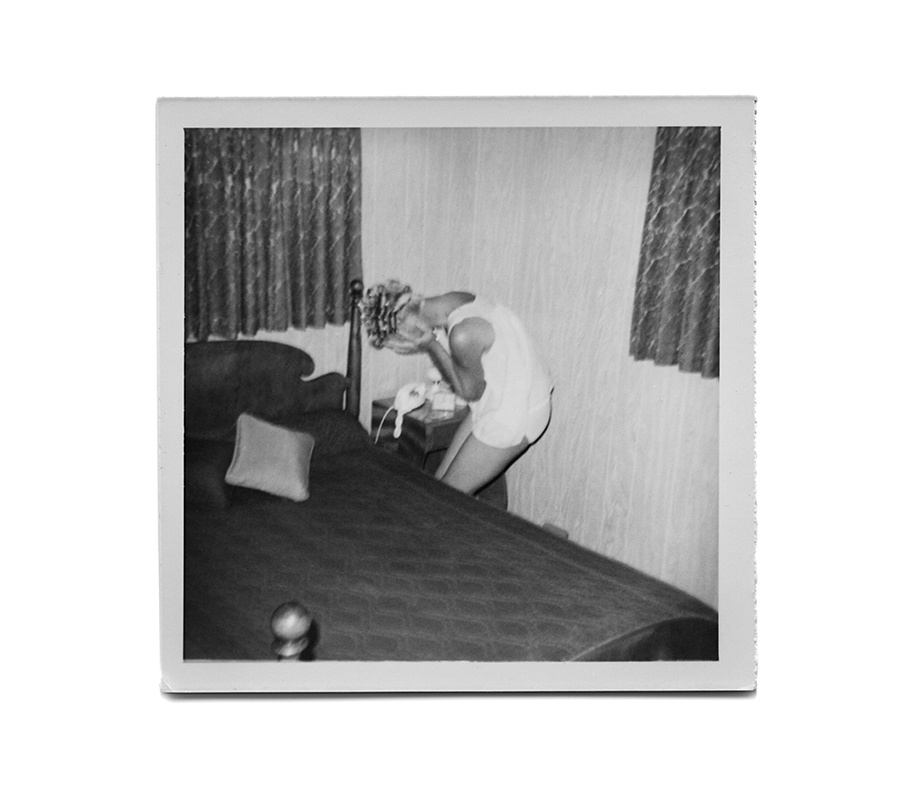

Mourning in Bed, from the Next of Kin Series | 2012

Fare for the Ferryman, from the Hereditary Estate Series | 2012

The Matriarch, from the Hereditary Estate Series | 2012

Confrontation, from the Next of Kin Series | 2012

Squall, from the Next of Kin Series | 2011

Panoptic Stain, from the Hereditary Estate Series | 2012

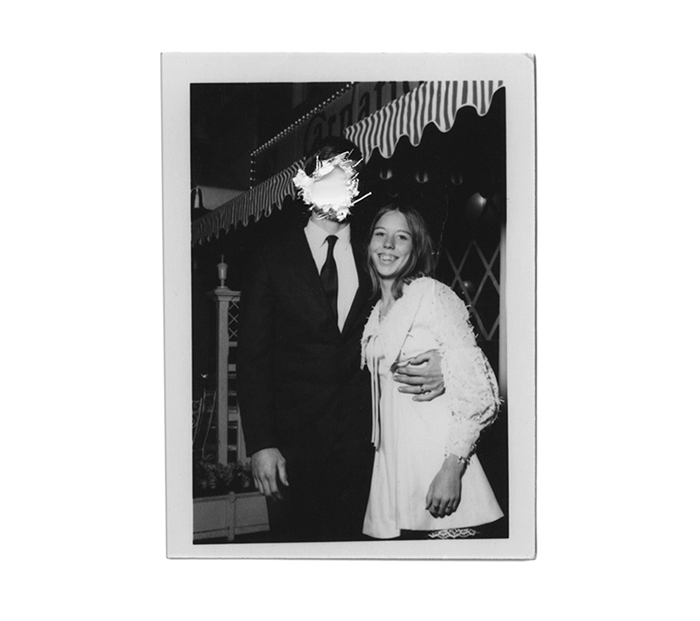

Untitled, from the Hereditary Estate Series; manipulated found snapshot | c. 1955

Untitled, from the Hereditary Estate Series; manipulated found snapshot | c. 1955

All images © Daniel W. Coburn